I’m 63 now, so the concept that I ought to nonetheless be collaborating in “journey sports activities” is maybe a bit ridiculous. Nonetheless, mountaineering has been a lot a part of my life for therefore lengthy that I nonetheless attempt to get out, typically for simple brief climbs on the gritstone cliffs close to my residence in Derbyshire. There are issues that I’ve accomplished in my youthful days that I’ve put behind me with out a lot remorse – I gained’t be climbing frozen waterfalls in New England once more, or winter climbing within the Lakes or Scotland. I do miss snowy mountains a bit, although I do know I’ll by no means be a critical alpinist. However there’s one number of cllmbing that I feel could be very particular, that I look again on with actual pleasure, and that I feel perhaps I ought to attempt to contain myself in as soon as once more, even when at a a lot decrease degree than earlier than. That’s mountaineering on Britain’s sea-cliffs, a department of the pastime with its personal distinctive environment and set of calls for.

I began mountaineering severely after I was 14 or so; at the moment it was my household’s behavior to spend each summer time in St Davids, Pembrokeshire, close to the place my mom had grown up. The shoreline of Pembrokeshire is spectacular – a succession of coves, headlands, and cliffs, pounded by the open Atlantic waves. On the time, the thought of climbing the cliffs of Pembrokeshire was in its infancy. Mountaineering on the granite cliffs of Cornwall was well-established, and the counter-cultural climbing scene of North Wales had created onerous and critical routes on the sea-cliffs of Gogarth, on Anglesea. However what little climbing on the cliffs of Pembrokeshire was recorded in a slim guidebook by Colin Mortlock, printed in 1974, not by the Climbers Membership or any of the institution sources of climbing info, however by a neighborhood publishing home extra related to postcards and wildlife guides than mountaineering.

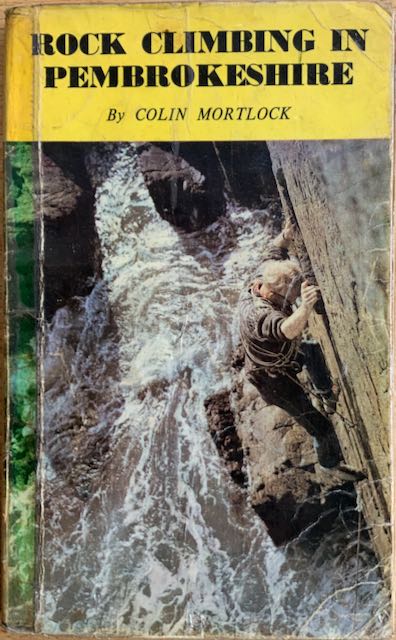

The primary ever guidebook to climbing in Pembrokeshire, by Colin Mortlock. Simply 150 pages lengthy (the present guidebook runs to five volumes), it usually failed within the primary perform of telling one the place the routes go (and, in a single or two instances, even the place the cliffs really are), however was a supply of nice inspiration. The quilt {photograph} is of Colin Mortlock himself climbing “Purple Wall” at Porthclais.

My creativeness was seized by the duvet of this e book, displaying Mortlock himself powering up a sheer, apparently overhanging, wall above a boiling sea. The route was referred to as “Purple Wall”, and was graded “extreme” – that was the sort of climbing I needed to do. In 1977 I persuaded my faculty pal and climbing accomplice Mark Miller to come back and stick with my household in Pembrokeshire so we may give this sea-cliff climbing enterprise a strive.

Mark and I had been, by that point, fairly assured climbers as much as grades of extreme, with some degree of primary competence at rope work and safety, and in possession of the essential gear – ropes, harnesses, the nuts and slings that had been cutting-edge on the time. We studied the guidebook and regarded on the image. It regarded steep – however certainly, if it had been that overhanging, the holds should be good. We’d accomplished routes like that on the gritstone cliffs of Derbyshire, we thought – powerful routes for the grade, however inside our grasp.

However we’d misjudged it. The quilt image turned out to wildly tilted; it’s an off-vertical slab, perhaps 70 levels or so, blessed with excellent sharp, incut finger holds. We romped up it. Extreme? It might barely be V. Diff within the Peak District! Nevertheless it stays one in all my favorite routes – I’ve in all probability accomplished it twenty instances since then. Few routes seize so fully the enjoyment of sea-cliff climbing at its friendliest, with easy accessibility to the bottom of the route, clear blue water sloshing gently beneath one’s toes, lichen and rock samphire on stunning pink rock, footholds and handholds in all the fitting locations.

Mark and I obtained higher and extra skilled at climbing. By the point we left faculty I used to be a assured chief of climbs VS in grade, tentatively making an attempt issues that had been a bit more durable. Mark had by power of will transformed himself into an excessive chief, with a specialism in daring, protection-less slabs. In the summertime earlier than I went to College, in 1980, we persuaded a comparatively new pal, Peter Carter, to come back with us to Cornwall and Devon. Or, extra precisely, we persuaded Peter to take us there – not too long ago discharged from the Royal Marines, he had the distinctive asset of proudly owning, and understanding methods to drive, a small van.

Our journey began on the very tip of Cornwall – on the granite cliffs of West Penwith. We did some superb climbs on the normal cliffs of stable granite, like Bosigran and Chair Ladder. Nevertheless it was on the return journey that our sea-cliff horizons had been really expanded. A bleak headland close to the north coast village of St Agnes is thought to climbers as Carn Gowla, with 300 foot cliffs falling vertically into the deep sea.

The route we selected was a HVS referred to as Mercury. The primary downside is attending to the bottom of the route – the one manner was to abseil. We tied two 150ft 9 mm ropes collectively, anchored them to a superb thread within the slope above the groove, and set off down. On the backside, a ledge about twenty toes above the waves, there’s an enormous sense of dedication – the best manner out is the route Mercury, all 270 ft of it. In the long run, the technical difficulties weren’t past us, although the publicity, dedication, and the doubtful, vegetated rock had been very removed from the pleasant crags of the Peak District.

One other spotlight of that journey was my first encounter with the spectacular surroundings on the stretch of coast north from Bude to Hartland. Often known as the Culm Coast, it’s composed of thinly bedded sandstones and shales which have been dramatically folded, after which sliced abruptly by the ocean. Not solely is it essentially the most dramatic coastal surroundings in England, it additionally supplies a wide range of nice climbs, starting from brief and stable sea-washed slabs to 400 foot climbs, virtually of mountain scale, on rock whose solidity isn’t above suspicion. I’ve returned to it repeatedly.

There’s one thing uniquely memorable, I feel, about sea cliff climbs, and even a long time on I vividly bear in mind the climbs and the folks I did with them with. On the Culm Coast there’s a 400 ft climb referred to as Wrecker’s Slab. The primary time I did it was with my faculty pal Jonathan Sharp, I feel only a few months earlier than he tragically died within the Alps. It wasn’t onerous, however its scale and looseness gave it fairly a fame, well-deserved.

In Pembrokeshire, amongst the cliffs north of St Davids, Trwyn Llwyd is a wonderful buttress of stable gabbro. I did Barad with Sean Smith; its crux felt like a VS gritstone jamming crack – 200 toes immediately above the ocean. Craig Coetan is a a lot simpler crag, above a bit inlet which attracts curious seals. In my teenage years I explored these light slabs with my father.

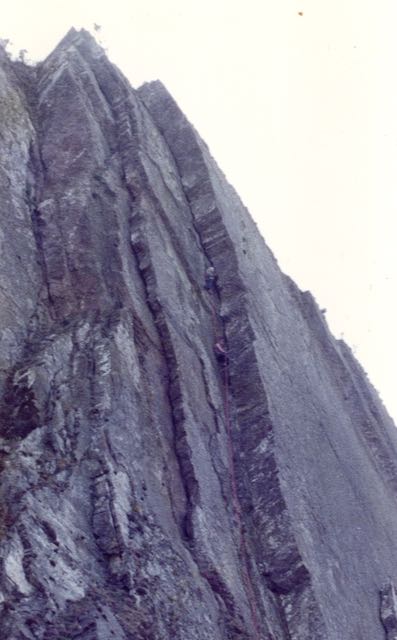

Again within the Culm coast, the toughest route I did was with my outdated and far missed pal, the late Mark Miller. Blackchurch is a crag with a sinister environment that solely lives as much as its identify; Archtempter is among the classics of the primary cliff – a hovering groove line now graded E3. Mark did the primary pitch, skinny and unfastened, and I led the widening crack above by way of an overhang. On the high, we up to now forgot ourselves to shake fingers.

Blackchurch, North Devon. The apparent groove is the road of “Archtempter”; the (simply seen) climbers are Mark Miller on the midway stance, and above him the creator, nearly to enter the overhanging part. It’s not a fantastic picture, however it does convey one thing of the demonic environment of this crag.

Searching for new routes supplies one other, exploratory dimension to sea-cliff climbing; I had many memorable journeys with Brian Davison, who believed that the aim of information books was to let you know the place to not climb. Within the Lleyn Peninsula, we did one of many earliest routes up Craig Dorys; we referred to as it “Error of Judgement”. Because the guidebook says: “It definitely was, an appallingly unfastened line”.

In North Pembrokeshire Penbwchdy is a protracted headland with a future of massive, vegetated cliffs. I’d been there with Jonathan Sharp however didn’t stand up something – we’d scrambled down a grassy slope, accomplished a 150 ft abseil to sea degree to seek out our manner ahead was to cross a deep however slender inlet on the stays of a wrecked ship. Not relishing the thought of balancing throughout on an outdated propeller shaft, over which waves had been breaking, we went again the way in which we got here.

The good pioneer of sea-cliff climbing, Pat Littlejohn, had a accomplished a route on the far finish of Penbwchdy, on a bit of cliff he referred to as New World Wall, accessed by a protracted low-tide sea degree traverse after the shipwreck crossing that Jonathan and I had balked at. Completed in 1974, I think Terranova, because the route was referred to as, hadn’t had quite a lot of repeats, given the awkward strategy. However Brian and I later discovered one other manner all the way down to New World Wall, with some cautious route discovering and a remaining scramble. Brian led a brand new route up this, which he referred to as “New Daybreak Fades”, at E4, a superb onsight lead up a steep groove.

One of the best new route I ever did was on the sandstone cliffs south of St Davids, a few miles east of Porthclais. A pamphlet describing new routes reported a brand new crag on the headland close to Caerfai, with a HVS referred to as “Amorican”, now a traditional and sometimes repeated route. I kicked myself – I’d walked previous that crag innumerable instances however by no means seen its potential. However to the fitting of the crack of Amorican is a sweeping concave slab of sandstone, unclimbed in 1984. Climbing with Mary Rack, I discovered a circuitous line; a skinny sloping crack demanded 20 ft of intricate and exact footwork, with solely tiny holds for the fingers. I referred to as it “Unsure Smile”.

Sea cliff climbing undoubtedly has extra hazard than the landward selection – unfastened rock, tidal situations, massive waves. One expertise in Cornwall was the closest I’ve (knowingly) come to dying. My climbing accomplice was José Luis Bermudez; we had been staying on the Climbers Membership hut at Bosigran, the place I bear in mind being hubristically superior, as skilled climbers and profitable younger teachers, to the occasion of college college students we had been sharing the hut with.

The subsequent day we went to Fox Promontory, a barely obscure granite headland on the south facet of the West Penwith peninsula. We scrambled down above the March seas to a sloping platform, perhaps 20 toes above the extent of the ocean. However freak waves do exist; I bear in mind seeing a wall of water coming in direction of me, then an enormous weight knocking me down and dragging me downwards throughout the tough granite. José had been on a better degree than me, I felt him seize me as I got here to a cease a couple of toes above the ocean. We hastened to climb out, me soaking moist, practically hypothermic by the point we obtained to the highest of the route, with the entire of the entrance of my physique grazed and bloody, feeling like I had been dragged throughout a cheese-grater.

Sooner or later in my 30s I realised I didn’t any extra have the bottle to do massive critical sea-cliff routes any extra. One memorable time out with Brian Davison in all probability confirmed this; he had his eye on an unclimbed sea-stack near Fishguard – Needle Rock. However to get to it we needed to unravel a 200 foot cliff, additionally unclimbed. We abseiled so far as a 150 rope would take us. We needed to descend the final 50 ft utilizing the ropes we had been going to climb with, so after we obtained to the hole between the cliff and the needle we needed to pull them down after us. Now we needed to stand up the sea-stack and down once more earlier than the route again to the primary cliff was minimize off by the tide, after which discover a new route on-sight to get again up the mainland cliff.

In the long run it was superb – Brian led a superb route up the sea-stack, which he named “For sure”. And there was a comparatively easy route up the primary cliff to be discovered, at about VS in grade. Brian is a wonderfully robust and resourceful climber; there’s no-one I might belief extra to get out of a sticky scenario, and there actually was nothing to fret about, however I may really feel myself shedding my cool and succumbing to nervousness and worry.

I feel these routes had been just about the final critical, excessive routes I’ve accomplished on sea-cliffs. However sea-cliff climbing doesn’t at all times need to be like that. There’s nonetheless pleasure available in light routes above quiet seas. And there’s no higher instance of that than the route I began this piece with, Purple Wall at Porthclais, nonetheless one in all my favorite routes anyplace.

The gentler facet of sea-cliff climbing. The creator on his umpteenth ascent of Purple Wall, Porthclais, close to St David’s; this image provides a way more correct sense of the character of the route than the duvet image of the Mortlock information!